What’s next for the Swinnie jigsaw

Earlier this year one of our foresters discovered a huge jigsaw piece while surveying for an upcoming land management plan.

The shape covers around 2 hectares and is one of three pieces found in the area.

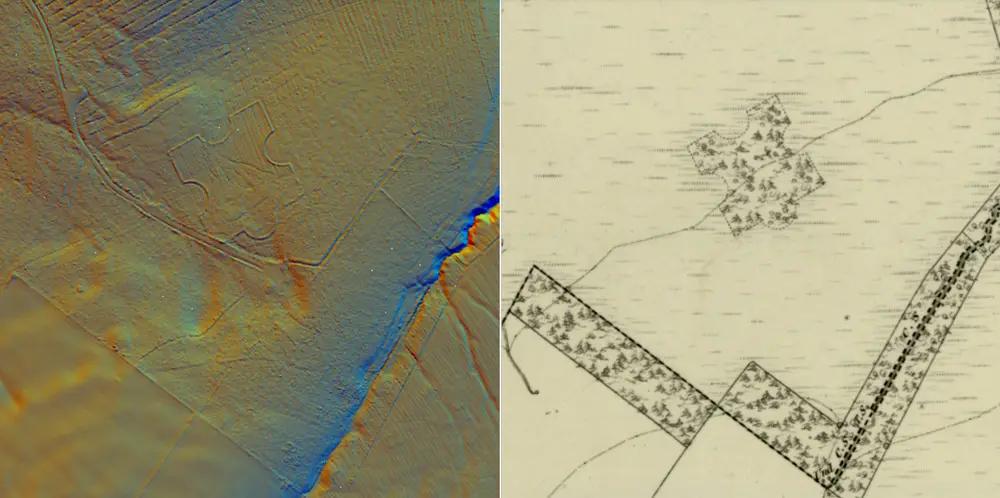

The irregularity was noticed during a desk-based assessment of all available aerial images and historic maps. This showed a distinct pocket of broadleaf trees inside a large plantation of productive spruce. With an on-site assessment of the area a distinct puzzle piece shaped feature was found lying within. Further assessment of historic maps revealed approximately 7 nearby similar shapes in the landscapes.

Roxburghshire Sheet XXVI, survey date 1858, publication date 1863

It turns out these areas were likely created in the 19th century as shelterwoods for livestock.

“The jigsaw piece shape is formed by a ‘woodbank’ - a raised embankment that in the very early days of forest management would define the woodland boundary. There would have likely been a ditch right next to the woodbank that was intended to protect the trees within from browsing damage”, said Tom Harvey, the Planning Forester for the area.

“The earthwork really jumps out of the LiDAR data available on the National Library of Scotland website” said Matt Ritchie, our in-house archaeologist.

“I had never seen a landscape feature of this size and shape before. It was clear that it was an old woodland boundary, but why the odd shape?”

Our initial press around these pieces resulted in many responses and ideas from across Scotland, including a local farmer who said they are called ‘stells’, shelters that were built to provide protection for sheep.

In the Borders, stells were usually built as circular drystone walls which the sheep could shelter inside, and that could double as stock enclosures. The Swinnie jigsaw piece gave the animals lots of options to hide from the elements, whichever way the wind was blowing.

Making the shapes an unusual blend of woodland heritage and agricultural archaeology.

From the National Library of Scotland

What’s next

Land management plans last for up to 10 years and make up the foundation of how we use the land. Foresters like Tom think about all the various opportunities and challenges when creating a plan, from soil types and species choice to ecosystem services and the historic environment. They put all this information together to create the best outcome for the area, with a vision spanning well into the future (as trees take a long time to grow!).

Matt works with planning staff, like Tom, to ensure we are respecting and considering the historic environment when creating our land management plans.

Sometimes that means providing access paths and interpretation, and sometimes it means using contemporary silviculture to help us plan around the archaeological feature.

Tom said that in the future they are looking to plant native conifer and broadleaf trees around the feature, but the existing healthy spruce crop will likely remain for the duration of the new plan, growing that little bit more every year.